How to efficiently store and modify text in memory. A poorly designed text buffer causes visible lag when typing; an efficient one provides a seamless experience

The text buffer is the programmatic representation of text in memory, any data structure capable of storing and modifying text

Approach 1: Raw String (Array of Characters)

The simplest approach: store text as a contiguous array of characters in memory

- Text stored sequentially in memory

- Compact and cache-friendly

- Direct indexing to any position

- Insertion:

- Identify insertion point at index

i - Shift all characters from position

ito end one position right - Insert new character at position

i

- Identify insertion point at index

- Deletion:

- Identify deletion point at index

i - Remove character at position

i - Shift all subsequent characters one position left to maintain contiguity

- Identify deletion point at index

With large files (hundreds of thousands of characters), every insertion/deletion triggers expensive shift operations. This causes visible lag, some decades ago this was acceptable, but modern users expect instant feedback

At last, It’s Excellent for static text, catastrophic for dynamic editing

Approach 2: Gap Buffer

Users don’t randomly insert characters throughout text, rather they type at a localized position. Instead of creating space for each character individually, create a large gap once and reuse it Structure:

- Contiguous array with a gap at the cursor position

- Track two values:

gap_start: offset where gap beginsgap_end: offset where gap ends (or usegap_start+gap_length)

[T][e][x][t][ ][ ][ ][h][e][r][e]

^gap_start ^gap_endInsertion at cursor:

- Place character at

gap_start - Increment

gap_start - No shifting required until gap is exhausted

Cursor movement:

- If moving cursor to new position, shift characters to relocate gap

- Local edits minimize shifting since users typically edit nearby text

Deletion:

- Decrement

gap_start(deletion before cursor) or incrementgap_end(deletion after cursor) - Update gap boundaries, no character shifting needed

Limitations:

- Not suitable for multicursor editing, only one gap exists

- Still faces performance issues with large files and frequent cursor jumps

- Works best for sequential editing patterns

Real-world usage: GNU Emacs still uses gap buffers today

Approach 3: Linked List

Text doesn’t need to be contiguous in memory, only on screen and in saved files. Fragment text into chunks stored anywhere in memory, linked together

Structure:

- Text divided into fixed or variable-size chunks (nodes)

- Each node contains:

- Text fragment

- Pointer to next node

- (Optional) pointer to previous node in doubly-linked list

Node1["Text "] -> Node2["buff"] -> Node3["ers"]

(addr: 0x100) (addr: 0x2A0) (addr: 0x150)Insertion:

- Locate target node by walking from head

- Break node at insertion point into two halves

- Create new node with inserted text

- Rewire pointers:

node1 -> new_node -> node2

Deletion:

- Locate target node

- Remove characters from node

- If node becomes empty, unlink it and update pointers

Limitations: We eliminated character shifting but introduced a new bottleneck: node traversal. Walking through nodes has linear time complexity, with long files or many edits, this causes the same lag we tried to eliminate

Approach 4: Rope (Binary Search Tree of Text Fragments)

A linked list is just a degenerate tree where each parent has one child. Using a binary tree structure dramatically improves traversal performance Structure:

- Text fragments stored in leaf nodes of a balanced binary search tree

- Internal nodes store metadata (subtree character count for indexing)

- Each node has at most two children

- Typically implemented as a red-black tree for guaranteed balancing

Root (total_len: 50)

/ \

Left (len: 23) Right (len: 27)

/ \ / \

Leaf1 Leaf2 Leaf3 Leaf4

"Text" " buffer" " using" " trees"Finding position (character at index k):

- Start at root

- Compare k with left subtree size

- If k < left_size: recurse left

- Else: recurse right with adjusted index

- Time: O(log n)

Insertion:

- Find target node in O(log n)

- Split node at insertion point

- Insert new node

- Rebalance tree (red-black tree operations)

- Update parent node metadata

Deletion:

- Find and remove characters from target node

- Rebalance if necessary

- Update metadata up the tree

Red-Black Tree Properties

Ensures worst-case logarithmic time by maintaining:

- Every node is red or black

- Root is black

- Red nodes have black children

- All paths from root to leaves have same number of black nodes

- Advantages:

- Dramatically faster than linked lists for large files

- Predictable worst-case performance

- Scales well to millions of characters

- Real-world usage:

- Zed editor uses a modified rope called “SumTree”

- The SumTree adds custom metadata aggregation for syntax highlighting and collaborative editing features

Approach 5: Piece Table (Hybrid Reference-Based Structure)

Most editing sessions start with existing file content, then apply incremental changes. Store original text separately from modifications and use nodes to reference fragments from both buffers

Structure:

- Two raw string buffers:

- Original buffer: Contains entire initial file content (read-only)

- Add buffer: Appends all newly added text

- Descriptor nodes (pieces) stored in a sequence:

- Each node contains:

source: Which buffer (Original or Add)start: Starting offset in that bufferlength: Length of text fragment

- Each node contains:

Original buffer: "Hello world"

Add buffer: " beautiful"

Piece table:

[Original, 0, 5] -> [Add, 0, 10] -> [Original, 5, 6]

Represents: "Hello beautiful world"Initial state:

Single descriptor: [Original, 0, file_length]

Insertion at position p:

- Locate descriptor node containing position p

- Split descriptor at p into two pieces

- Create new descriptor:

[Add, add_buffer.length, insertion_length] - Append inserted text to Add buffer

- Link three pieces:

piece1 -> new_piece -> piece2

Deletion at position p for length L:

- Locate descriptor(s) spanning the range

- Split descriptors at boundaries

- Remove/trim affected descriptors

- Note: Original text never modified, just change references

Advantages:

- No data duplication: Original file content stored once

- Efficient undo: Keep history of descriptor states

- Fast operations: Text buffers are read-only arrays (cache-friendly)

Limitations: With descriptors in a linked list, we face the same traversal problem as Approach 3

Approach 6: Piece Tree (VS Code’s Solution)

Combine piece table’s memory efficiency with binary tree’s traversal performance Structure:

- Piece table architecture (Original + Add buffers)

- Descriptor nodes stored in red-black binary search tree instead of linked list

- Each tree node stores:

- Piece descriptor (source, start, length)

- Subtree metadata (total character count, line breaks for rendering)

- Red-black tree pointers and color

Tree maintains:

- Character count for O(log n) position lookup

- Line break count for O(log n) line number lookup

- Balanced structure for worst-case guarantees

- Finding position k:

- Traverse tree comparing k with left subtree’s character count

- Descend left or right accordingly

- O(log n) time

Insertion:

- Find target piece in O(log n)

- Split piece and create new descriptor

- Insert into tree with rebalancing

- Update ancestor metadata

Deletion:

Similar to insertion, split pieces, remove descriptors, rebalance tree

Real-world usage: VS Code’s current text buffer implementation

Comparative Analysis

| Data Structure | Insert/Delete | Find Position | Multicursor | Memory Overhead | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw String | O(n) | O(1) | No | None | Static text display |

| Gap Buffer | O(1) amortized | O(1) | No | Minimal | Small files, sequential editing |

| Linked List | O(1)* | O(n) | Yes | Moderate | Not recommended |

| Rope | O(log n) | O(log n) | Yes | Moderate | Large files, frequent edits |

| Piece Table | O(1)* / O(log n) | O(n)* / O(log n) | Yes | Low | Memory-constrained environments |

| Piece Tree | O(log n) | O(log n) | Yes | Moderate | Production text editors |

| Rope/Piece Tree: |

- Gains: Excellent scalability, predictable performance, feature support

- Loses: Memory overhead, implementation complexity

Real World Usage:

- File size expectations: Small files → gap buffer sufficient

- Feature requirements: Multicursor → need tree-based structure

- Memory constraints: Limited RAM → piece table architecture

- Undo/redo needs: Full history → piece table excels

knobs to Tune

Node size tuning:

- Too small: Excessive tree overhead

- Too large: Wasted memory, slower splits

- Typical: 512-1024 bytes per leaf node

Balancing strategy:

- Red-black trees: Guaranteed O(log n), complex implementation

- AVL trees: Stricter balancing, faster reads, slower writes

- B-trees: Better cache locality, more complex

Memory management:

- Pooling small allocations reduces fragmentation

- Reusing nodes avoids allocation overhead

- Copying vs. referencing trade-offs

Real-World Implementations

VS Code

VS Code started with a naive line-based model: an array of strings, one per line

lines: [

"function hello() {",

" console.log('world');",

" return 42;",

"}",

]- User tried to open a 35 MB file with 13.7 million lines

- Created one

ModelLineobject per line (~40-60 bytes each) - 600 MB overhead for a 35 MB file → 17x memory bloat

- Splitting file to create line array was slow due to string operations

Approach 1: Basic Piece Table

The solution: don’t store actual text, store references to buffers

class Buffer {

value: string; // Actual text

lineStarts: number[]; // Cached line break positions

}

class Node {

bufferIndex: number; // Which buffer

start: BufferPosition; // Offset in buffer

end: BufferPosition; // End offset in buffer

}

class PieceTable {

buffers: Buffer[]; // Multiple 64KB chunks

rootNode: Node; // Tree of references

}Why multiple buffers?

- Node.js

fs.readFilereturns 64 KB chunks - Can’t concatenate into single string, V8 has 256 MB string limit (later 1 GB)

- Solution: Push each chunk directly as new buffer, create node pointing to it

Insertion:

- Find node containing position p

- Split node into left and right portions

- Append new text to “added” buffer

- Create new node pointing to added buffer

- Rewire:

left_node -> new_node -> right_node

Result: O(1) append + one node split

Memory efficiency:

- Original file size ≈ memory used (no duplication)

- New edits appended (linear with edit count, not file size)

- Massive improvement over line array

Limitations:

- Finding “line N” requires traversing all nodes to find which contains it

- Complexity: O(N) where N = number of nodes

- With 1000 edits in a 64 MB file: 1000 nodes traversed

Approach 2: Red-Black Tree + Cached Metadata

The insight: binary tree traversal is O(log n), and we can cache what we need

A red-black tree diagram showing node coloring and structure for balancing in a binary search tree

class Node {

bufferIndex: number;

start: BufferPosition;

end: BufferPosition;

// Cached metadata for subtree

left_subtree_length: number; // Total chars in left subtree

left_subtree_lfcnt: number; // Total line breaks in left subtree

// Red-black tree pointers

left: Node;

right: Node;

parent: Node;

color: 'red' | 'black'; // For balancing

}Why red-black tree specifically?

- AVL trees: Stricter balancing, faster reads, but slower writes (more rotations)

- Red-black trees: More relaxed balancing, faster writes/edits

- Critical for text editing: edits are frequent, reads are scattered

Algorithm: Finding line N

function findLine(lineNumber) {

current = rootNode

lines_seen = 0

while (current is not leaf) {

lines_in_left = current.left_subtree_lfcnt

if (lineNumber <= lines_seen + lines_in_left) {

current = current.left // Target in left subtree

} else {

lines_seen += lines_in_left

current = current.right // Target in right subtree

}

}

// Now current is leaf containing target line

// Use node's lineStarts array for final lookup

return current.getLineContent(lineNumber - lines_seen)

}Time complexity:

- Tree traversal: O(log N) where N = nodes

- Final line extraction: O(1) using cached line Starts

- Total: O(log N)

Approach 3: Critical Optimization - Avoid Array Copies

The discovery: Don’t create new lineStarts arrays when splitting nodes

Naive approach (3x slower):

// BAD: Creates new array

let node = {

lineStarts: [0, 25, 50, 75, 100, ...] // 1000 elements

}

// Split into two nodes

let left = { lineStarts: array.slice(0, 500) } // Copy!

let right = { lineStarts: array.slice(500) } // Copy!Optimized approach:

class BufferPosition {

bufferIndex: number; // Which line break array

index: number; // Index in that array

remainder: number; // Offset past that line break

}

// No array copying—just store references

node1.start = BufferPosition { bufferIndex: 0, index: 100 }

node1.end = BufferPosition { bufferIndex: 0, index: 150 }

node2.start = BufferPosition { bufferIndex: 1, index: 0 }

node2.end = BufferPosition { bufferIndex: 1, index: 50 }Q Why No Native C++ Implementation?

A The JavaScript ↔ C++ boundary is expensive

JavaScript code (Toggle Line Comment):

for each selected line:

content = textBuffer.getLineContent(lineNum) // Cross boundary!

analyze(content)

apply changes

Problem: One C++/JS round trip per line

× 1000 lines = 1000 boundary crossingsAdditional constraints:

- Must return JavaScript strings (require allocation/copying)

- V8 strings are not thread-safe

- Can’t use V8

SlicedStringorConstStringoptimizations - Would require rewriting all client code to minimize boundary crossings

Zed Editor

Core requirement: Thread-safe snapshots for

- Concurrent syntax highlighting (Tree-sitter on background thread)

- Concurrent language server protocol (LSP) operations

- Multi-user collaborative editing

- Asynchronous saves and backups

Zed’s architects realized: The rope data structure is not just about text, it’s about composability and concurrency

SumTree

It’s a B+ tree with custom summary aggregation

It’s a B+ tree with custom summary aggregation

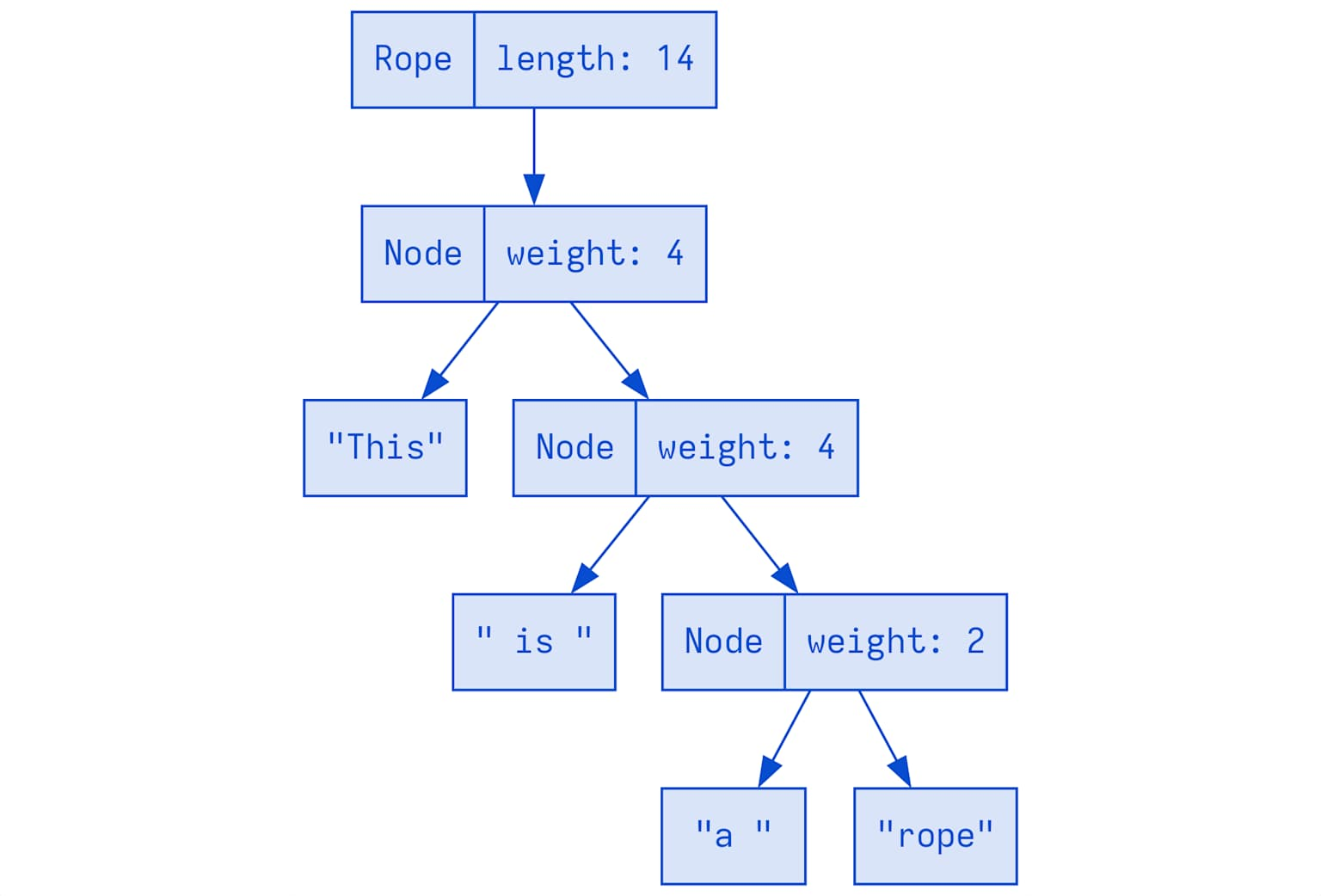

A rope sum tree representing the string ‘This is a rope’ with node weights and hierarchical breakdown for efficient text operations

Definition:

type SumTree<T> = B+Tree where:

- Leaf nodes: Multiple items of type T

- Internal nodes: Summary of child summaries

- Traversal: Based on summary dimensionsZed’s Rope is literally:

type Rope = SumTree<Chunk>

type Chunk = ArrayString<128> // Up to 128 chars, stored inline

struct TextSummary {

len: usize, // Total characters

lines: usize, // Total line breaks

longest_row_chars: usize, // Longest line length

// Custom fields can be added

}Q Why B+ Tree Instead of Binary Tree?

A

- Binary tree (Piece Tree):

Root / \ L1 R1 / \ / \ L2 L3 R2 R3- 2 children max

- More nodes to traverse for same data

- B+ tree (SumTree):

Root / / | \ \ N1 N2 N3 N4 N5 (each has 16-32 children) / \ / \ / \ / \ / \ ...leaves...- 16-32 children per node (tunable)

- Fewer levels to traverse

- Better cache locality (more data per node)

- More flexible: Easy to add multiple summary types

Multi-Dimensional Cursor Seeking

This is where SumTree becomes extraordinary → seek along one dimension, aggregate along multiple

Example: Convert character offset to (row, column)

- Traditional approach (O(log n) but requires two passes):

Pass 1: Seek to offset 26 → find node

Pass 2: Count lines to that position → row/column- SumTree approach (O(log n), single pass):

let cursor = rope.chunks.cursor::<(usize, Point)>();

// Two dimensions: offset and point

cursor.seek(Offset(26));

let (offset, point) = cursor.summary();

// Returns BOTH offset AND aggregated lines/columns in one traversal!How it works internally:

TextSummary tracking:

len: 72 (total chars)

lines: 5 (total line breaks)

longest_row_chars: 22

Cursor seeks along "len" dimension

while aggregating "lines" and "longest_row_chars":

Root [len: 72, lines: 5, longest: 22]

├─ Left [len: 38, lines: 2, longest: 19]

│ (Don't descend—len: 38 > 26, but check if subtree contains it)

│

├─ Right [len: 34, lines: 3, longest: 22]

│ (Descend here? No, 38 < 26+34, so check left first)

│

└─ Descend left of Right subtree...Skip entire subtrees when summary shows they can’t contain the target

Immutability + Reference Counting = Snapshots

// Original rope (10MB file in memory)

let rope1 = load_file("sqlite.c");

// Send snapshot to syntax highlighter thread

let rope_snapshot = rope1.clone(); // NOT a deep copy!

// Just bumps Arc reference count

spawn_thread(|| {

syntax_highlight(rope_snapshot) // Background thread works

});

// Meanwhile, main thread edits rope1

rope1.edit(10000, 50000, "new text");

// rope_snapshot unaffected—rope nodes are immutable!Zed’s leaf nodes (Chunks) are quasi-immutable:

// Chunk is ArrayString—stores string inline (not on heap)

// Each chunk: max 2*CHUNK_BASE = 128 characters

// When appending 50 chars to rope:

if last_chunk.len() + 50 <= 128 {

last_chunk.mutate_and_append(50); // Mutate last chunk only

} else {

create_new_chunk(); // New chunk, old chunks untouched

}Result:

- Most operations: O(1) append to last chunk

- Occasional: Create new chunk + rebalance tree (still O(log n))

- Snapshots: Free (just Arc increment)

SumTree Traversal: The Mathematics

Key insight: Monoid homomorphism

For any traversal dimension D:

- Each node has summary.D

- Child summaries can be added together to get parent summary

- Traversal maintains invariant: left_sum < target ≤ left_sum + current

Example: Convert UTF8 offset to UTF16 offset

─────────────────────────────────────────

TextSummary can track:

utf8_len: 72

utf16_len: 68

lines: 5

Seek to UTF8 offset 26:

cursor.seek(Utf8Offset(26))

Result: utf16_offset = cursor.aggregate(Utf16Dimension)

= 25 (UTF16 uses different encoding for some chars)

All in O(log n) with single tree traversal!Real-world use case: LSP protocol

- Language servers expect UTF16 offsets

- Editors think in UTF8

- SumTree converts on-the-fly during tree traversal

Everything is a SumTree in Zed

20+ uses of SumTree beyond just Rope:

| Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Rope | Text content |

| File list | Project tree |

| Git blame info | Blame annotations per line |

| Chat messages | Message ordering/indexing |

| Diagnostics | Error/warning positions |

| DisplayMap | Fold positions, line wrapping, inlay hints |

| Syntax tree | Tree-sitter AST integration |

DisplayMap example (where text meets rendering): |

struct DisplayMap {

text: SumTree<TextChunk>,

// Folding metadata

folds: SumTree<Fold>,

// Line wrapping metadata

wraps: SumTree<LineWrap>,

// Inlay hints (LSP)

inlays: SumTree<InlayHint>,

// Tab stops, indent guides...

metadata: SumTree<Metadata>,

}

// Query: "What's the display line count?"

// Answer: Sum all wraps in SumTree—O(log n)SumTree isn’t optimized for text editing specifically, it’s optimized for building composable, queryable, concurrent data structures